Management should be determined by the patients’ readiness to try to quit and should be tailored to individual needs.

If the patient is ready to quit (i.e., in the next 30 days), a treatment plan should be devised which includes counselling and pharmacotherapy if appropriate. Additionally, a ‘harm reduction’ approach could be considered for those not wishing to quit immediately, using for example a nationally approved ‘pre-quit’ nicotine replacement therapy.[#national-institute-for-health-and-care-excellence-nice-2013,#the-royal-australian-college-of-general-practitioners.-2011]

A patient who recently quit (i.e., in the past 6 months) requires continued support and encouragement, and reminders regarding the need to abstain from all tobacco use—even a puff. A patient who has been off of tobacco for more than 6 months typically is relatively stable but often needs to be reminded to remain vigilant for potential triggers for relapse.

Evidence based smoking cessation programs such as Quitline, or local smoking cessation programs increase the likelihood of quitting. These are particularly important for:

- People who are at high risk of relapse

- Patients who have made multiple serious quit attempts

- Adolescent smokers

- Pregnant smokers

- Patients with co-existing psychiatric conditions

- The Smoking cessation guidelines algorithm provides an overview of the recommended approach to smoking cessation.

Non pharmacological management

The non pharmacological approach to smoking cessation should include the following components:

Behavioural interventions that have been shown to be effective for supporting smoking cessation suggest:

Pharmacological management

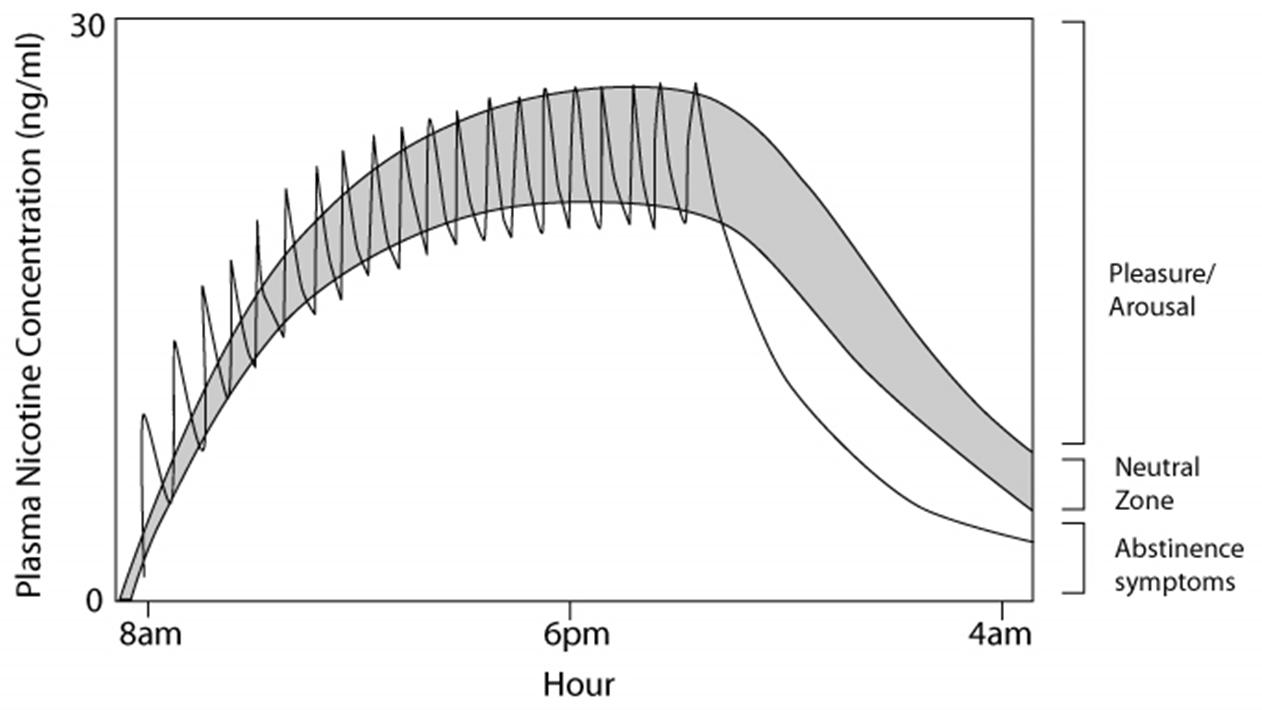

Adding pharmacological management to counselling significantly improves abstinence rates.[#fiore-mc-jaen-cr-baker-tb-et-al.-2008] Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) can be delivered in a number of ways. Peak plasma concentrations are higher and are achieved more rapidly when nicotine is delivered via cigarette smoke compared to other NRT formulations. Among the NRT formulations, the nasal spray has the most rapid absorption, followed by the gum, lozenge, and inhaler. Absorption is slowest with the transdermal formulations. Because NRT formulations deliver nicotine more slowly and at lower levels (e.g., 30–75% of those achieved by smoking), these agents are far less likely to be associated with dependence when compared to tobacco products.[#choi-jh-dresler-cm-norton-mr-et-al.-2003,#fant-rv-henningfield-je-nelson-ra-et-al.-1999,#schneider-ng-olmstead-re-franzon-ma-et-al.-2001]

See Nicotine dependence for more information on the physiological basis of NRT.

The table below summarises the pharmacological approach to smoking cessation.

Table 2: Overview of nicotine replacement therapies benefits and safety concerns

| Medication |

Comments |

| Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT) |

- More effective as combination therapy i.e., patch + oral

- Using therapeutic nicotine is always safer than continuing to smoke

- All forms of NRT can be used by patients with stable cardiovascular disease, but should be used with caution in people with recent myocardial infarction (MI), unstable angina, severe arrhythmias and recent cerebrovascular events

- Growing evidence for the safety of NRT in smokers with acute coronary syndromes and NRT can be used in this situation under medical supervision. See Smoking cessation algorithm

|

| Varenicline |

- Most effective monotherapy medication for the treatment of nicotine dependence

- Initial research had suggested an increase in cardiovascular events in smokers. However, this has been found to be statistically and clinically insignificant in subsequent research

- Safe in stable cardiovascular disease

- Initial post marketing reports of increased neuropsychiatric symptoms, but subsequent meta-analysis has shown no evidence of increased suicidal events, depression or agitation compared to placebo. However, it is recommended that prescribers ask patients to report any mood or behaviour changes

|

| Bupropion |

- Antidepressant found to significantly increase smoking cessation rates

- Shown to be effective for smokers with depression, schizophrenia and cardiac disease

- Contraindicated in patients with a history of seizures, eating disorders and those taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors

- Current recommendations suggest it should be used with caution in people taking medications that can lower seizure threshold, such as antidepressants, antimalarials and oral hypoglycaemic agents

|

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology

Treatment & Management

Treatment & Management

Exercise

Exercise

Medications

Medications

Psychosocial Issues

Psychosocial Issues

Patient Education

Patient Education

Behaviour Change

Behaviour Change

Clinical Indicators

Clinical Indicators

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology

Treatment & Management

Treatment & Management

Exercise

Exercise

Medications

Medications

Psychosocial Issues

Psychosocial Issues

Patient Education

Patient Education

Behaviour Change

Behaviour Change

Clinical Indicators

Clinical Indicators

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology

Treatment & Management

Treatment & Management

Exercise

Exercise

Medications

Medications

Psychosocial Issues

Psychosocial Issues

Patient Education

Patient Education

Behaviour Change

Behaviour Change

Clinical Indicators

Clinical Indicators